stangmx13

not Stan

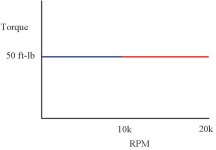

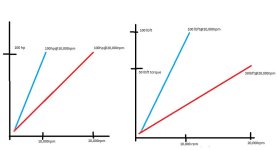

the HP curves make it just as obvious that the Blue bike will accelerate faster if they have the same gearing. they both start at 0HP and peak at 190HP, one at 10k and the other at 20k. so the Blue HP curve is twice as steep and has twice as much HP at every RPM (>0) for a 0-50MPH run. since everything else is the same, twice as much HP == twice as much acceleration just like with torque. the result might be slightly harder to infer from a HP curve, but its still there.

this also does a good job of showing that torque numbers arent shit either. your rate of acceleration is just as dependent on gearing and tire radius. so having a pissing contest over torque numbers is still not very effective. just drag race and get it over with.

this also does a good job of showing that torque numbers arent shit either. your rate of acceleration is just as dependent on gearing and tire radius. so having a pissing contest over torque numbers is still not very effective. just drag race and get it over with.